The Slingshot

In this twenty-fifth installment of his memoir, Memories of a Boy Growing Up in Blackville, fifteen year old Pat Fournier learns a lesson in empathy after making a slingshot with his friend Gary Gillespie.

THE SLINGSHOT

Written by Pat Fournier

July 1962 – fifteen years old

My friend Gary Gillespie sniffled and rubbed the back of his hand against his broad nose.

“If you can get some rubber from a red inner tube from a bicycle tire”, he said, “I guarantee you, you’ll have the best slingshot ever.”

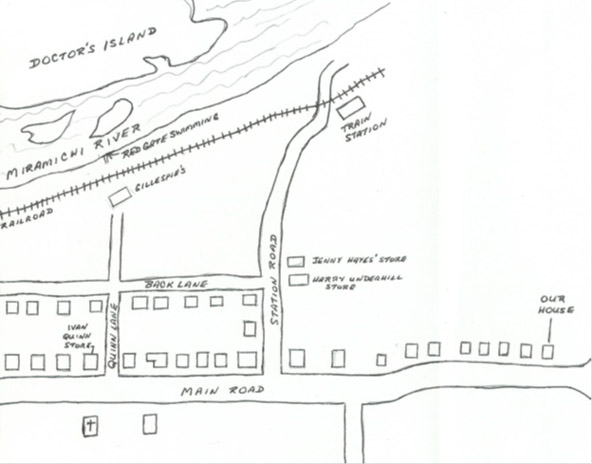

We were walking back home from school together, and we stopped just past Ivan Quinn’s store. While I continued up the Main Road to home, Gary would go down Quinn Lane to the Back Lane, then down to his house by the railroad tracks.

“Black rubber’s good”, he continued, “but the rubber from a red inner tube is the best, ‘cause it’s more elastic than black. Only trouble is, it’s so friggin’ hard to find a red inner tube. But holy dyin’, it makes a great slingshot!”

So we agreed to be on the lookout for the elusive red rubber inner tube, and to share the rubber, if we found any. I made regular trips to Blackville’s public dump, back in the woods up the dusty Bartholomew Road. But while I found some empty beer bottles that I could turn in at Jenny Hayes’ store, my trips didn’t yield a treasure of red rubber inner tube. Nor did my searches among the tires dumped behind Fred Crawford’s Irving or Lounsbury’s Esso. But about a week later Gary gave me a couple of nice strips of red rubber tubing that he had managed to find somewhere, and they were perfect for making a slingshot.

My RCMP jackknife

The first thing I did was take a walk up the nearby Howard Road to search out a nice small maple tree with a “Y” shaped branch. The Howard Road, just up the Main Road from our house, was bordered by forests on both sides of the dirt road, with lots of maple trees among the fir, spruce and pines. I walked slowly up the dirt road, every so often jumping down the ditch and up the other side to investigate a promising looking maple tree. I didn’t have to go very far before I found a small tree with a perfect “Y” shaped branch, with both arms of the branch being of equal thickness. I pulled my Mountie jackknife out of my jeans pocket, and cut down the branch, leaving a long section of the main branch below the fork, and headed back home.

Once back home, I sat on the back steps and set to work at fashioning the perfect slingshot. I first cut each upright arm of the Y-shaped fork to equal lengths of about four inches long, and trimmed the thicker bottom branch to just the right length for a good solid hand-grip. After peeling off the bark, I used my jackknife to cut a quarter-inch notch all around the wood near the top of each fork of the slingshot. After stretching an end of the strip of rubber tightly around one notched end, I tied the rubber together with a string, so that the rubber couldn’t slip out of its notched position. Then I did the same for the other side.

Next, I threaded each of the other ends of the rubber strips through a slit cut into each side of the canvas tongue cut out of an old sneaker, folded the rubber up on itself, and tied it tight with string. And it was finished!

I tried it out with a rock placed in the sneaker-tongue pouch, and the rock went whistling up in the air and into the woods behind the shed. Like Gary had said, the red rubber made one heck of a good slingshot! After a few more practice shots, I set off to find something good to shoot at.

I tried it out with a rock placed in the sneaker-tongue pouch, and the rock went whistling up in the air and into the woods behind the shed. Like Gary had said, the red rubber made one heck of a good slingshot! After a few more practice shots, I set off to find something good to shoot at.

The mid-afternoon sun was sweltering hot as I walked up the Bartholomew road. Every now and then a grasshopper would jump out of the dusty grass and weeds by the road side, his wings clicking madly as he sped by in a ragged flight pattern. There were some scraggly blueberry bushes along the side of the ditch, but they had been covered with the fine dust that settled on them from the cars that drove up the road heading to the public dump, so the berries weren’t worth picking to munch on. A couple of crows cawed loudly as they circled around the trees back at the edge of the field where Chris Underwood brought his cows to graze. The sun continued to beat down through cloudless blue skies, and I sweated in my summer tee shirt.

A power line insulator on a telephone pole cross beam

I continued to practice my aim by shooting rocks at the necks of broken beer bottles that lay in the ditch, and at the glass insulators at the tops of the telephone poles.

But I wanted a better challenge. Something alive and moving.

Around a turn about a quarter mile up the road, an old logging truck road led back into the woods, and I could hear a squirrel chattering loudly back in the trees. The tires of heavy pulp trucks had once gouged deep ruts in the soft earth of the logging road. Once the ruts were filled up with puddles from rain and melting snow, but the sun had long ago dried up the water, leaving behind dried cakes of mud that looked like curved pieces of broken pottery.

I only walked a short distance down the grassy center between the ruts of the logging road when I saw him. The red squirrel was sitting in plain sight on a thick branch, maybe twenty feet up a big pine tree. He looked down at me as he perched on his haunches and nibbled on something in his small front paws.

Being cautious not to move too quickly, I took a rock out of my pocket and placed it in the pouch that dangled at the ends of the red rubber. Then, holding the rock tightly in the pouch between my thumb and the knuckle of my first finger, I stretched the rubber back, aimed carefully, and let the rock fly. And it hit him! But the squirrel didn’t move! I knew for sure that he was hit, but he just continued to sit there – – although he did drop the pinecone seed he had been munching on.

Being cautious not to move too quickly, I took a rock out of my pocket and placed it in the pouch that dangled at the ends of the red rubber. Then, holding the rock tightly in the pouch between my thumb and the knuckle of my first finger, I stretched the rubber back, aimed carefully, and let the rock fly. And it hit him! But the squirrel didn’t move! I knew for sure that he was hit, but he just continued to sit there – – although he did drop the pinecone seed he had been munching on.

I put another rock in the pouch, pulled back hard, and let it fly. Again, a direct hit! But he still didn’t move! What was he waiting for? Why didn’t he scamper away? Was it possible that he couldn’t move, because his legs or ribs were hurt so bad from the rocks hitting him? He made a few “chip, chip” sounds, and continued to sit in the same spot, where the thick branch sprouted out of the big pine.

And then I just stood there too, looking up at him, and I thought: “Hey, this isn’t fun anymore!”

I didn’t bother to put another rock in the slingshot. Instead, I wrapped the rubber tight around the forks of the slingshot, turned, and walked back a few steps. I looked back up at him, and he was still sitting there, making little squeaky chirping sounds, his bushy tail curling backward behind him. And now I wondered if he was going to be able to make it back to his home.

I walked back down the logging road, and out to the Bartholomew. I didn’t bother taking any more target practice as I walked back home. The bands of red rubber remained wound tightly around the slingshot, and all the way home I was guiltily replaying in my mind what I had done, and worrying about the little injured squirrel up in the pine tree.

When I got back home, I went in the kitchen and sat down in Dad’s rocking chair by the side of the kitchen stove. I held the slingshot hidden under my cupped hands in my lap. Mom was working at the counter, just a few steps away, but I didn’t know whether she looked over and saw me holding the slingshot, with a downcast look on my face.

A few years ago when I was smaller, and she and Dad came home from shopping down in Newcastle, she would always somehow know if us kids had been acting up while they were gone. And when we asked her how she knew, she’d always say: “A little bird told me”. And while that sounds silly, the thing is, she did know if we’d done something wrong! So while she didn’t say anything to me now, I wondered if somehow she knew what I had done. And I knew that she would be disappointed in me.

A few years ago when I was smaller, and she and Dad came home from shopping down in Newcastle, she would always somehow know if us kids had been acting up while they were gone. And when we asked her how she knew, she’d always say: “A little bird told me”. And while that sounds silly, the thing is, she did know if we’d done something wrong! So while she didn’t say anything to me now, I wondered if somehow she knew what I had done. And I knew that she would be disappointed in me.

Even though it was a hot summer day, a good fire was burning in the wood stove as Mom prepared to make supper. As I sat there in the rocking chair, I was torn with indecision as to whether or not to destroy the slingshot. I felt so bad about hurting that little squirrel that I knew I didn’t want to hurt another living creature again. And I figured if I kept the slingshot, the temptation would always be there to go ‘hunting’ and find a live target.

On the other hand, I knew this was the best slingshot I’d ever have, and if I destroyed it, who knows if I’d ever get some more red rubber to make another one? Also, what would I say if Gary asked me what I did with the red rubber he gave me?

Finally, I made my decision. I had to destroy it. I was ashamed of what I’d done. I wasn’t a hunter, and knew I couldn’t stand to hurt another little helpless animal.

The flames licked up from the burning wood as I lifted a lid off the wood stove with the poker. And I dropped the best slingshot I’d ever make, down into the flames.

Click here for more installments of “Memories of a Boy Growing Up in Blackville”.

Does anyone know where I can find some school class photos from 1958 to 1964 my picture would be in?

Thank you for the story. I remember the same things just like it was yesterday. I’m 66-years old now and love to journey back to when life seemed a lot less hectic than today. Snaring rabbits, gathering maple sap from the big maple tree at the Red Gate, and making a pile of rocks in the middle of the river to dive off are a few of the many memories to keep me company in the dreams of my long final sleep.